Nashville Tennessee has earned the nickname “Music City, U.S.A.” for good reason. And although for most Americans, the city is known primarily for being a hub of Country Music, Nashville houses a rich history for all kinds of music traditions.

Nashville’s Fisk University is well-known for being one of the nation’s most treasured Historically Black College/ Universities and for the internationally-acclaimed Fisk Jubilee Singers. One of America’s most storied choral ensembles, the group has provided a window into the history of Negro Spirituals for 144 years. But even that preservation wouldn’t have been possible without the work of famed musician, composer, conductor and musicologist John Wesley Work Jr.

Born the son of a slave and coming of age during the Reconstruction era, John Wesley Work Jr. was surrounded by great music. His father, the first John Wesley Work, was a singer and choir director. So when he came to Fisk University as a freshman in 1890, he knew that his acceptance into Fisk’s music program was a great accomplishment in itself. Founded in 1871, the Fisk Jubilee singers had quickly become legendary, as their tour to raise funds for the university had already taken them to notable performances for President Ulysses S. Grant at the White House, and even Queen Victoria in England.

But Work Jr. brought the Fisk Jubilee singers to the world in a way not previously imagined, and one that we are thankful for today. In 1909 Work, now a Faculty member at Fisk and conductor of the group, landed upon critical music history when he agreed to a recording project for the Fisk quartet. Here’s more on its significance, via Archeophone…

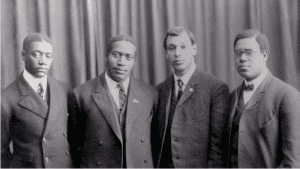

The quartet of Work, first tenor, James Myers, second tenor, Noah Ryder, first bass, and Alfred King, second bass, made ten sides for Victor at the end of 1909, records that signaled a sea change in the kind of entertainment Americans could purchase for the home. As Tim Brooks points out in his recording notes accompanying Mr. Seroff’s essay, most of the recorded fare of the previous 20 years with a “jubilee” theme or African-American influence was parodic and often demeaning. With the Fisks, now black art, history, and culture were literally getting a fair hearing. Songs such as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “There Is a Balm in Gilead” were well-known, and the Fisks give masterful performances, while “Little David, Play on Yo’ Harp / Shout All Over God’s Heaven,” “Roll Jordan Roll” and “The Great Campmeeting” became instant favorites that the group were called on to perform regularly in concert.

This recording, made by the sons of emancipated slaves, provides a critical link to the traditions of American Negro Spirituals. Thanks to Work and the other singers, it and the recordings that followed stand as a witness to our musical past. They’ve even found new relevance via digital restoration and platforms like YouTube.

Work’s time on the Fisk faculty was somewhat short… only 1909-1916. In that time, he managed to not only commission a series of landmark recordings, but wrote an impressive document of the history being sung at the institution. Work’s Folk Song of the American Negro stands today as one of the most important ethnomusicological contributions of the 20th Century for its exhaustive research of the various African-American music traditions from that time and before. Without John Work Jr., much of this history could have been lost.

Last but certainly not least, John Wesley Work Jr. was a gifted composer in his own right. Besides writing songs in the Negro Spiritual style and substantial choral arrangements, Work also composed some treasured art songs. Soliloquy is a favorite of his for the tender poetry and ascendant vocal line, proving some of the best elements from Work’s musical fortitude. Here is my performance of Soliloquy from 2010.

The contributions of John Wesley Work Jr. are not only a pillar of African-American music history, but continue to enrich the lives of all American music today.

(The 1909 Fisk Jubilee Quartet, with John Wesley Work Jr. to the far right. Photo credit: Doug Seroff via NPR)